Although I was only twelve when The Devil Wears Prada was released, I vividly recall feeling utterly dissatisfied with its ending. Over the years, I’ve rewatched the movie countless times, and the feeling has only grown stronger. WHY ARE YOU DOING THIS??? I want to shake Andy (Anne Hathaway) as she throws her phone into the Fontaine des Mers. The movie concludes neatly, with what one might consider a satisfying resolution. (Spoiler alerts ahead for those who haven’t seen the film.) Andy leaves Miranda stranded in Paris with no assistant, gives her free designer clothing to Emily out of the goodness of her heart (if only to assuage her guilt about going to Paris in her place), gets a humble job as a journalist at a small newspaper, reunites with her kind (albeit insecure) chef boyfriend, and we can assume she lives happily ever after. Even at the tender age of twelve, the notion that this was an ideal ending felt like deception to me.

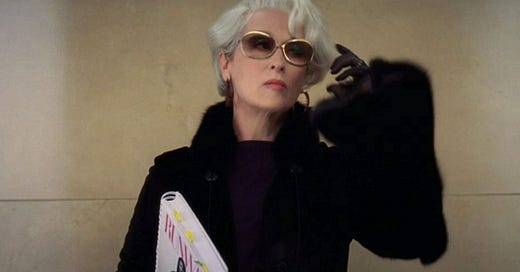

During the iconic cerulean blue sweater monologue, Miranda Priestly (brilliantly portrayed by Meryl Streep) addresses Andy, saying “it’s sort of comical how you think you’ve made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry, when in fact, you’re wearing a sweater that was selected for you, by the people in this room”. This movie, of course, is one about success, its true nature, and its very definition. But it is also a profound exploration of the fashion industry and its importance.

The Devil Wears Prada was inspired by Lauren Weisberger’s novel, which recounts Weisberger’s experiences as an assistant to Anna Wintour, the Editor-in-Chief of Vogue. In 2006, Vogue held immense influence, and it’s hard to exaggerate its impact. When Miranda delivers the aforementioned line to Andy in the movie, it’s not inaccurate to say that Anna Wintour, inadvertently, dictated what most of us purchased and wore, whether we were consciously aware of it or not.

In the era before social media, fashion magazines were the arbiter of culture. They dictated what was cool and what was trending, and Vogue, in particular, was the authority on them all. Designers relied heavily on Anna’s opinion, as it could make or break a collection and, consequently, a season. As we all know, what ends up in the collections and on the runways eventually finds its way into our closets.

For the entire first half of the film, Andy is made to feel foolish for failing to recognize the significance of her job, her boss, and the fashion industry as a whole. However, as the story progresses, she undergoes a remarkable transformation. She loses weight, cuts her hair, and starts wearing samples from the fashion closet. As she elevates her appearance, improves her performance, and gains confidence, her relationship crumbles, her social life changes, and she begins to feel disconnected from her long-time friends. Initially, she would lament about her boss and coworkers at Runway, but she starts to empathize with them and even defends Miranda. She brings her friends generous gifts from work, and they gladly accept them before mocking her for her newfound dedication to her job. And as for her boyfriend, is he genuinely upset about her demanding schedule, or is he patronizing and insecure? Anyone who has ever had a demanding job understands the toll it can take on relationships, but Andy’s boyfriend, Nate (played by the charming Adrian Grenier), is at times just unsupportive.

So, it begs the question: if the movie featured a male lead and a male-dominated industry, would the ideal ending be one in which the protagonist throws away everything he has worked for in order to pursue a seemingly morally superior job? Would he reconcile with a jealous, unsupportive, and less successful girlfriend? While Andy compromises her integrity by agreeing to go to Paris instead of Emily, despite knowing how much it means to her, she witnesses Miranda’s betrayal of Nigel and decides she needs to leave fashion and Runway behind. The movie portrays Runway and its gatekeepers as the antagonists at the beginning, but you begin to see Andy get swept up in the glamour, and simultaneously the humanity in Miranda.

To my impressionable, 12-year-old mind, I perceived Andy as emerging as a confident and empowered individual. I noticed the transformation in Andy’s appearance—her elevated hairstyle, stylish clothing, and composed posture—which mirrored the intelligence, work ethic, and drive she had always possessed. I yearned for an ending where Andy remained unapologetically at Runway, learning from Miranda. Not to emulate her petulant behavior, but because I witnessed her influence on Miranda and the magazine’s culture. I recognized in her the potential to be a positive force at the magazine. I wanted to believe that Andy could reconcile with Emily, and that a woman doesn’t have to betray her most trusted subordinates, like Miranda did to Nigel, to advance her career or protect herself. I didn’t want Andy to end up with a man who was clearly intimidated by her success and newfound social status.

The notion that women face two distinct paths: isolation, loneliness, and success at another’s expense, or mediocrity, was a profound disappointment to me, even then.

***Author’s note, though this sounds like a scathing review, The Devil Wears Prada remains one of my favorite movies***

That’s an interesting take on the ending, from what I remember Andy’s ambition was always to write and she saw the Runway position as a potential route into fashion journalism. The question is how long would she have to remain Miranda’s assistant before she got an opportunity to write? She became a very good assistant, would Miranda have let her transfer to writing for the magazine? By leaving she stayed true to her ambition and the reference from Miranda certainly helped her secure the job on the paper. Her chef boyfriend should have been more supportive, she was well rid of him… One of my favourite films too, it will be interesting to see the direction the sequel takes.